Graylings are easy to spot when flying, but they seemingly vanish once settled, blending perfectly into the background.

Spot the Grayling!

© Collin Gilles, iNaturalist

© karitelo, iNaturalist

© Miroslav Skála, iNaturalist

© Golfopolikayakl, iNaturalist

© Pavel Kacl, iNaturalist

Graylings are large and distinctive butterflies that fly in strong loops. Once settled, their cryptic colouring makes them hard to spot. They keep their wings closed to make themselves look smaller. They also hide the eyespots on their forewings by tucking them under their hindwings. Sometimes, if they feel threatened by a predator, they will open their wings to show their wing spots. In addition, they are known to settle facing the sun to minimise the shadow they cast.

© Simon Oliver, iNaturalist

X

CLOSE

The word cryptic – descended from the Greek kruptikos – means concealed, hidden, secret, or occult. Zoology focuses on the first two definitions and means “serving to conceal or camouflage.” Cryptic plumage, usually subtle patterns of soft browns or greys, is a defensive adaptation; artfully-arranged stripes, spots, or shading breaks up the structural lines of an animal, rendering it visually indistinct.

Description

A Grayling Butterfly’s extraordinary camouflage, by Suzanna Crampton

Their wings are tan and dark brown above, with washed-out orange markings. The underside of their forewings is orange, and their hindwings have an intricate grey-and-black pattern.

The combination of orange and brown markings, with two large eyespots on the underside of the forewing and one smaller eyespot on the hindwing, is unique to the Grayling.

© Simon Oliver, iNaturalist

In the Millennium Atlas of Suffolk Butterflies (2001), Richard Stewart noted that

‘Another feature of the Grayling’s behaviour is its habit of landing on different parts of human clothing., literally from footwear to hats. This is probably to search for human perspiration on hot day. …In my own experience, this habit is more common in the Grayling than for any other British species….

Interestingly, he also thought there was ‘no immediate threat to this species in Suffolk’ and suggested that work of the Sandlings Project and heathland restoration in the Brecks might extend the Grayling’s breeding range.

They are endemic to Europe and are primarily seen in the coastal areas. They are typically found in dry habitats with warm climates, such as sand dunes, salt marshes, cliffs in coastal regions, heathlands, limestone pavements, scree and brownfield land. Colonies prefer areas with little vegetation and bare, open ground, with spots of shelter and sun. In Suffolk they are associated with open heathland in the Sandlings and Breckland.

However, due to habitat loss, their numbers have decreased significantly, and they are a Biodiversity Action Plan priority species.

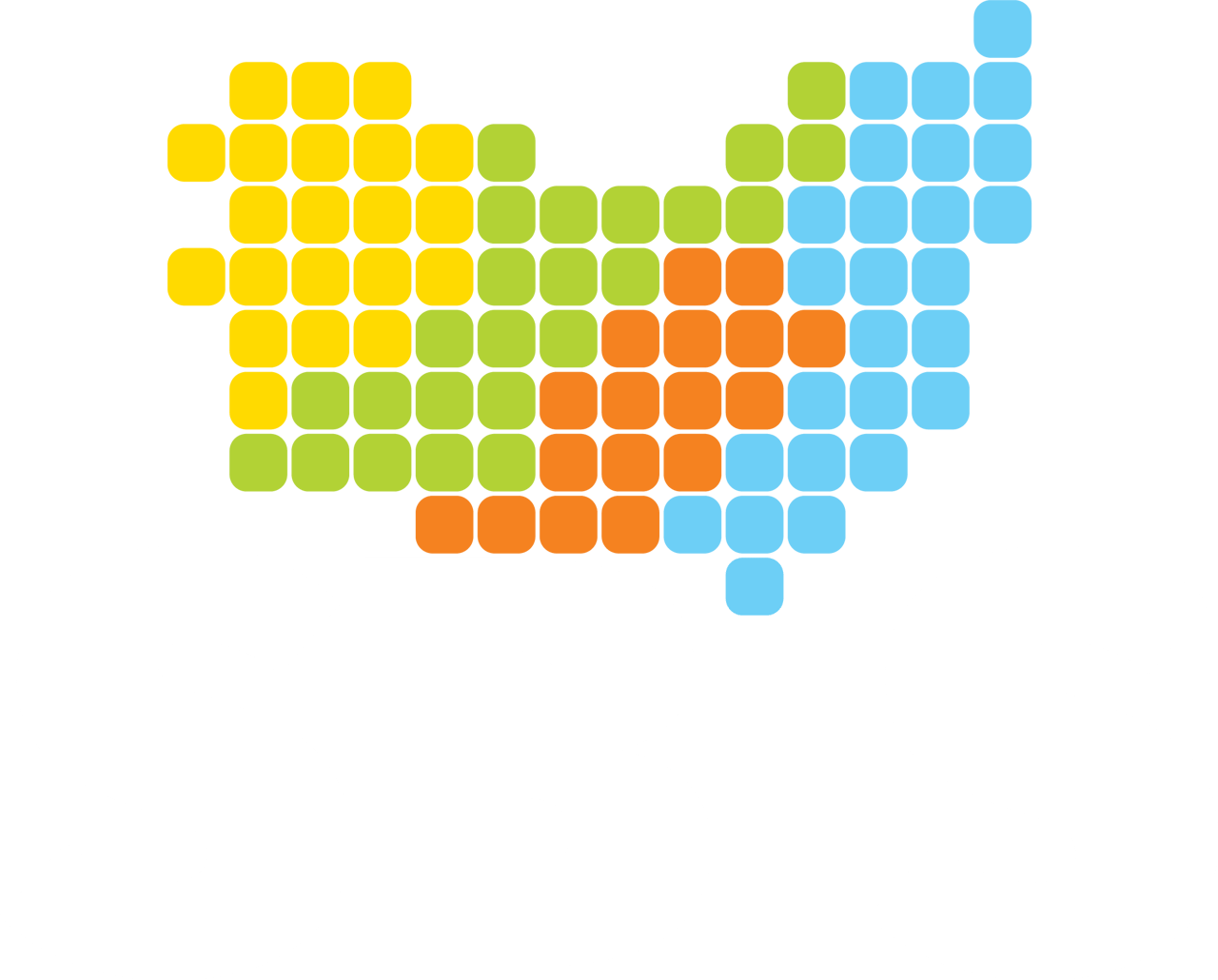

Distribution in Suffolk

All records

The first map shown has all the records from our database. However, it does not reflect the current status of the species in the county.

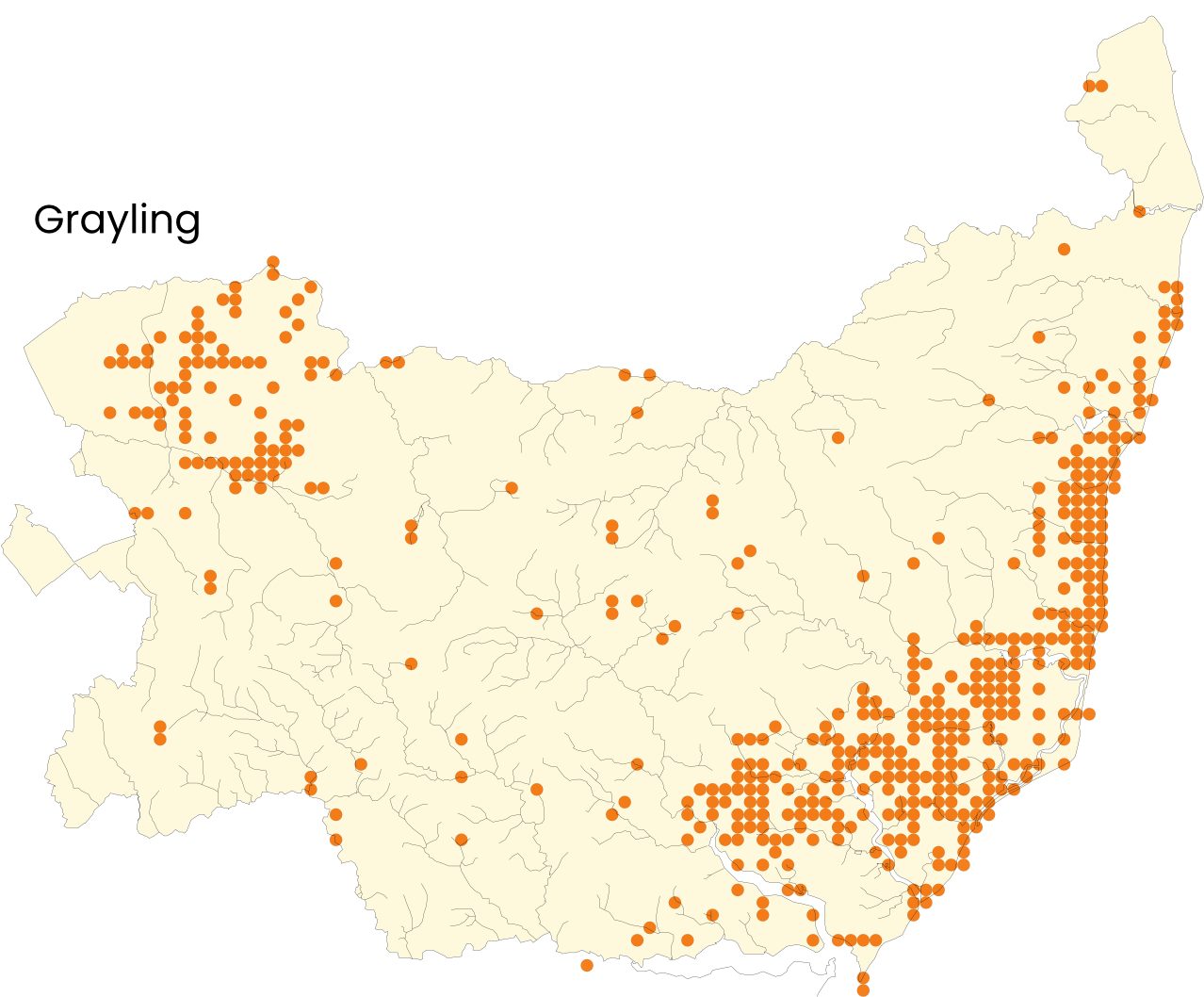

This second map, from the Suffolk Butterfly Report 2021, Suffolk Natural History Vol. 58 shows how much their numbers have declined recently (-40% decrease nationally over the last ten years, -71% in the previous 45 years).

It represents the distribution of Graylings recorded in 2021 and clearly shows the county divide, with the Breckland habitat in the west and the Sandlings in the east. They are now struggling in the county and appear to be almost lost in the west. Loss of habitat, intensification of farming methods, along with misuse of pesticides have no doubt had a major impact on this specialist of heathland.

However, according to the report, fewer Graylings were recorded in the east of the county and more in the north-west, compared with 2020. This is good news as the Breckland populations are more fragile than those in the Sandlings. The highest count of 2021 was 40, at Upper Hollesley Common."

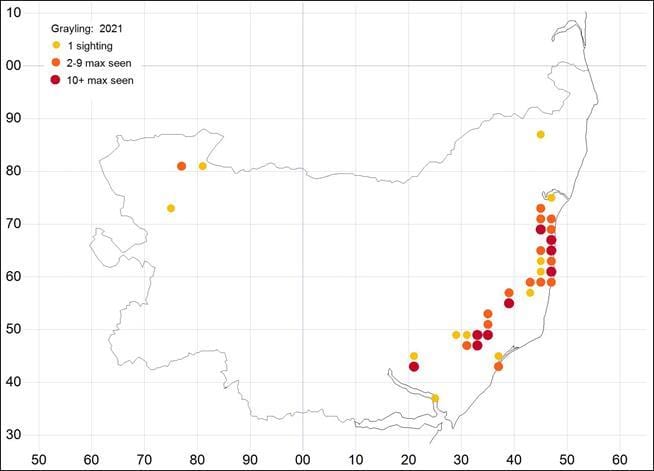

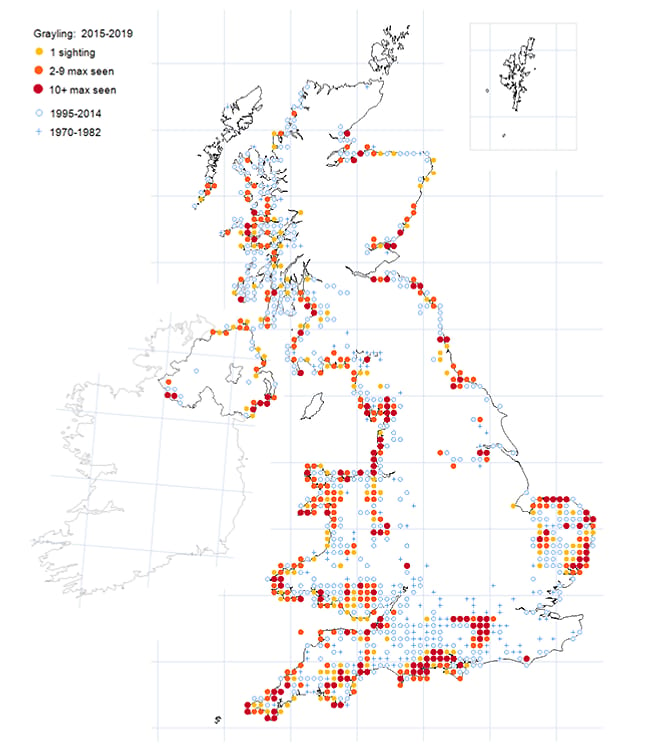

This map, taken from the Butterfly Conservation Atlas of UK Butterflies 2015-2019, puts the Suffolk losses in a national context.

Lifecycle

Grayling Butterfly (dance) - The Scottish Highlands - July 2022, by John S Nadin

Finding a mate

Graylings only have one generation per year. A female chooses a mate based on the egg-laying quality of his territory to give her eggs a higher chance of survival. A good site will also give her male offspring an advantage when they reach adulthood, boosting their ability to win and defend high-quality breeding territories. All this allows her genes to spread further.

© Simon Oliver, iNaturalist

Males engage in flight performance competitions for the best sites. Initially, each male flies upwards in a spiral motion, trying to get above and behind the other. They then begin an alternating sequence of dives and climbs. The male that can reach the highest position will win the territory. He will fly up to investigate passing butterflies to decide if he needs to defend his territory or begin courting a female.

© Peter Kennerley, iNaturalist

Courtship

Female Graylings only mate once, so selecting the best possible male, based on his territory, courting dance, and pheromones, is crucial for reproductive success.

Both butterflies settle on the ground, and his multi-layered and complex courtship dance begins with him landing behind her and making short movements around her until they face each other. If she is uninterested, she flutters her wings. However, a receptive female remains still, encouraging him to continue his dance.

© Lars Willighagen, iNaturalist

He starts by rhythmically raising and lowering his wings, revealing and hiding the orange patches on the underside. He then briefly flicks his wings open and shut and bows to the female while slowly bringing his wings together, moving the sex brands on his forewings under her antennae. The scent scales from the sex brands release pheromones to help seduce the female, and he moves behind the female for mating.

© Peter Eeles www.ukbutterflies.co.uk

Did you know?

Unlike many other butterfly species, the pupa (sometimes called a chrysalis) is formed below the soil surface.

Egg-laying, Larvae and Pupation

Single white eggs are laid from July to September. As they mature, they darken to a pale yellow and hatch two and three weeks after being laid.

Once hatched, the tiny and cream-coloured caterpillars feed on the tender tips of grass blades. They grow slowly and have four moults. First and second-instar larvae feed until mid-to-late summer and then hibernate during the third instar. The fourth instar resumes feeding in the spring, and the final instar larvae are nocturnal, hiding deep in the base of grass tussocks in the daytime. By June, they are fully grown and spend most of their time basking in the sun on bare ground or rocks.

Pupation is in a silk-lined cavity, just below the surface of the ground, where the caterpillars spin their cocoon. The pupa (or chrysalis) is formed between June and August, and the adult butterflies emerge around 4 weeks later.

For a fuller description of their lifecycle, please visit UK Butterflies.

© Peter Eeles www.ukbutterflies.co.uk

© Windrifter, iNaturalist

Did you know?

The female doesn’t usually lay directly on the food plant but on nearby dead vegetation, such as a dead grass stem.

A female Grayling laying an egg, by Stickybeak.

The larvae feed on grasses such as Sheep’s-fescue, Red fescue, Bristle bent and Early hair-grass. They occasionally feed on coarser grasses such as Tufted Hair-grass and Marram.

Adults take nectar from various plants, including Bird’s-foot Trefoil, Bramble, Carline thistle, Bell Heather, Marjoram, Red Clover, Teasel, Thistles and Buddleia.

Diet

© Michał Brzeziński, iNaturalist

Grayling Butterfly Hipparchia semele, by Steve Cross

Graylings prefer to live in open, sunny habitats to regulate their body temperature. They can be seen moving to spread the sun’s warmth evenly over their body.

If they get too cold, they lean over to expose their side to the sunlight, raising their body temperature by up to 3°C. If they get too warm, they stand on their tiptoes, turning to face the sun so that most of their bodies are shaded. This can lower their body temperatures by up to 2.5°C.

In this way, males can optimise their flight performance, which is vital for defending their territories and finding a mate.

© Leon Van Der Noll, Flickr

Thermoregulation

Meadow Brown Maniola jurtina: Wing Span Range (male to female): 50-55mm

Speckled Wood Pararge aegeria: Occurs in woodland, gardens and hedgerows. Wing Span Range (male to female): 47-50mm

Wall Lasiommata megera: Found around the coast. Wing Span Range (male to female): 44 - 46mm

Gatekeeper Pyronia tithonus: Wing Span Range (male to female): 40-47mm

Large Heath, Coenonympha tullia: Not found locally. Wing Span Range (male to female): 41mm

Small Heath Coenonympha pamphilus: An inconspicuous butterfly whose wings are always closed when at rest. Wing Span Range (male to female): 34-38mm

The Field Studies Council had an excellent Guide to UK Butterflies.

Find out more about Graylings

- Butterfly Conservation

- European Butterflies by Christopher Jonko

- European Butterflies by Matt Rowlings

- Guy Padfield’s European Butterfly Page

- Learn About Butterflies by Adrian Hoskins

- Lepidoptera and their Ecology by Wolfgang Wagner

- Moths and Butterflies of Europe and North Africa

- UK Butterflies

- UK Butterfly Monitoring Scheme