From a diffuse body – consisting of a network of fine filaments extending through the soil – grow the striking and ephemeral fruiting bodies of the Magpie Inkcap.

Fungi are neither plants nor animals but in their own kingdom. Surprisingly, they are more closely related to animals than plants. The mushrooms we are used to seeing are fruiting bodies, the equivalent of a flower. The fungus is hidden in the soil as a vast network of thin tubes called mycelium.

© Ken Owen, Flickr

Description

Cap

The cap is a pale, elongated finger-like shape (7cm wide) that unfurls into a black and white cone around 8cm wide. It has a dark background with white, fuzzy patches, resembling the plumage of a magpie, that turns from brown/grey to black and then deliquesces (melts).

Gills

The lamellae (gills) are very close together. In young specimens, they are white, then turn pink to grey to brown until they become black and deliquesce to release the spores.

© Katya, Flickr

Stem

The stem is white and narrow (6–15 mm). It is usually hollow and has a white movable skirt. Growing to 12–20cm long and tapering slightly towards the top. The stem has scales or fine fibres that form a snakeskin effect near its base. Sometimes, it can appear grey or black if stained with spores.

Flesh

The flesh is whitish with a fibrous, watery consistency and often has an unpleasant odour. It is poisonous.

© Gail Hampshire, Flickr

Taxonomic history

The Magpie Inkcap was first described in 1785 by Jean Baptiste Francois Pierre Bulliard, who named it Agaricus picaceus. In 2001, DNA analysis showed that many of the fungi in the genus Coprinus were only distantly related to one another. The Magpie Inkcap was moved into the genus Coprinopsis.

Etymology

Coprinopsis – looks similar to fungi in the genus Coprinus, which means ‘living on dung’. Picacea – from the Latin name for Magpies, Pica pica.

© Frank Vassen, Flickr

Filmed by Neil Bromhall over three days with an exposure interval of 5 minutes.

Shaggy Inkcap

The Shaggy Inkcap (Coprinus comatus) has a white cap with white scales, unlike the Magpie Inkcap's black cap with white scales.

Similar species

© Steffen Zahn, Flickr

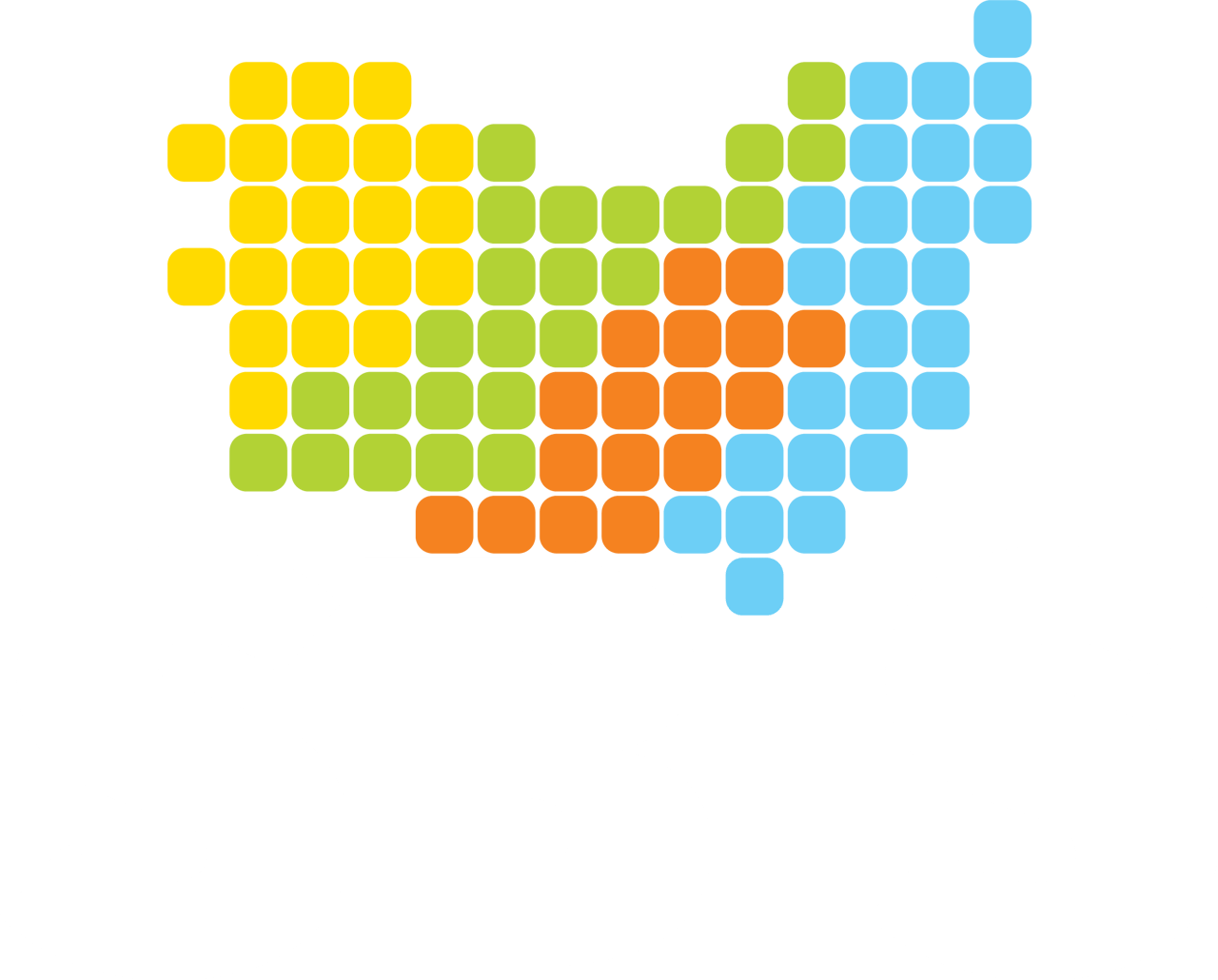

They are infrequent across the UK and commonly found alone or in small diffuse groups. Magpie Inkcaps occur most often in deciduous woodland, particularly under Beech trees and less frequently under oaks. They are mainly restricted to alkaline areas.

As you can see from the map, they are not well recorded in Suffolk, and we would love to receive more records. You can enter records directly on our website.

Visit the Norfolk Fungus Group website for a better representation of its frequency. They are a more active recording group, however, it is still rarely seen with only four spotted in 2022.

Distribution in Suffolk

Lifecycle

Fruiting body

When the fruiting body first emerges from the soil, the cap is white and egg-shaped with a serrated edge. The white skin begins to split as it grows, revealing the dark background.

The stalk grows, raising the cap into the air, which opens into a bell shape.

Towards the end of its life, the cap darkens and flattens. The brim rolls up, and it begins to deliquesce, dripping black liquid containing the spores.

© Frida Eyjolfs, Flickr

A closely related fungus, a Shaggy Inkcap, deliquescing.

© Dr Hans Gunter Wagner, Flickr

Did you know?

The black liquid formed when they deliquesce can be used as an ink. Although it apparently, develops a fishy smell, which might be a bit offputting!

Underground life

Little is known about the underground network of filaments that make up the main fungal body. However, we do know that they are essential for soil structure, fertility, and the global carbon cycle.

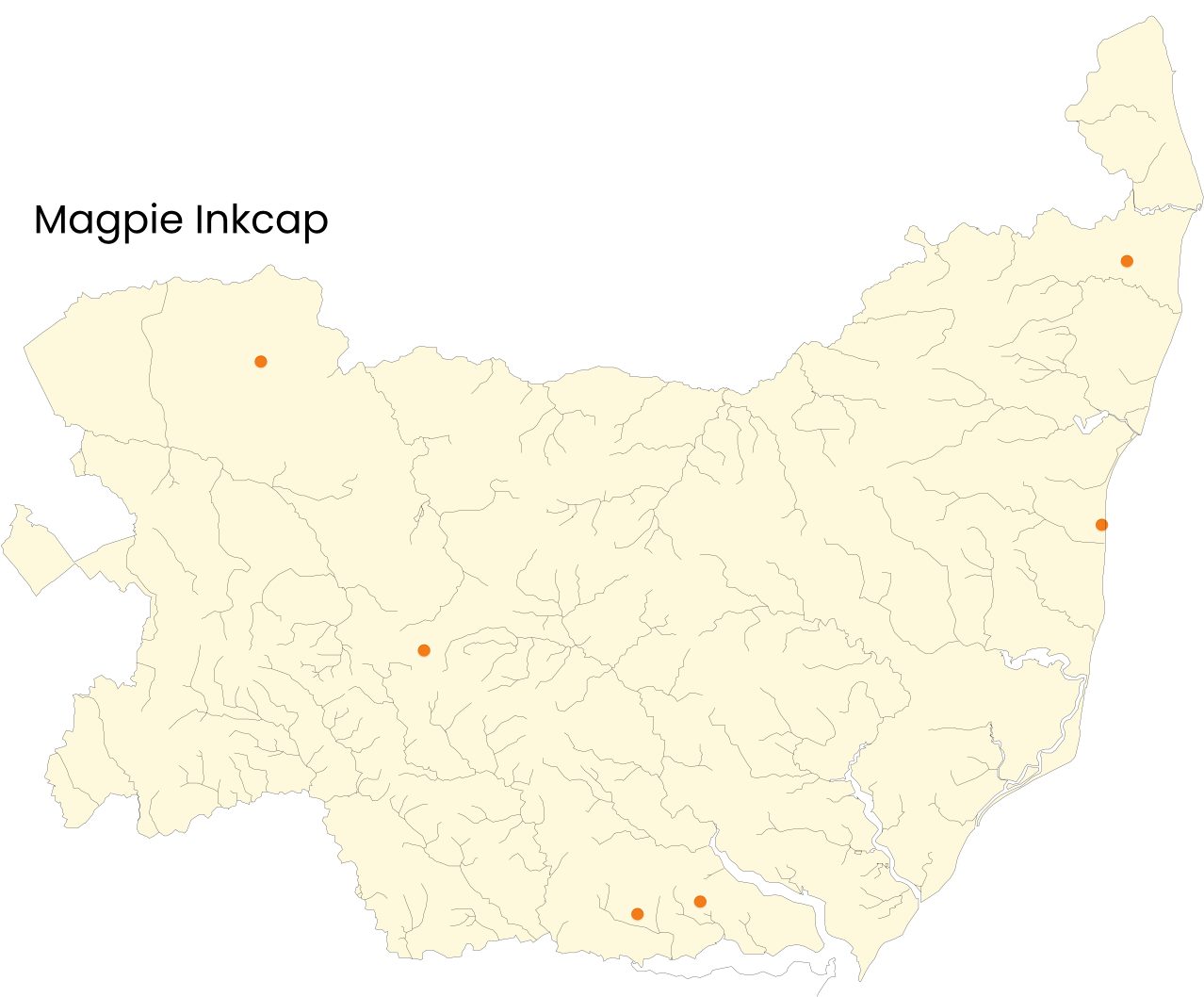

The thin tubes (hyphae) are 2-3 micrometres wide and act similarly to plant roots, growing through the soil to find nutrients.

New studies are beginning to reveal some of the mysteries. In a 2021 study, researchers created an obstacle course to discover more about fungi’s strategies when searching for food. Seven species of litter-decomposing fungi navigated constrictions, sharp turns and obstacles in the study. Researchers found that fungi had more variety in their growth patterns than plant roots.

In The secret life of fungi: how they use ingenious strategies to forage underground, Edith Hammer & Kristin Aleklett noted, “Some had hyphae that grew densely but extremely far and very straight, without exploring their surroundings (the marathon runner). Others grew slowly but constantly for months, meandering past complicated turns and corners (the snake). Others still branched heavily, filled up almost all free spaces, and with incredible force broke themselves through solid parts of the chips (the zombie).”

A 50-micrometre human hair intersected by a 6-micrometre filament. Hyphae are half this width at just 2–3 micrometres wide. Saperaud/wikicommons, CC BY-SA

Certain situations gave fungi a hard time. Repeated sharp turns led some to get stuck in corners, while others lost their sense of direction after growing around a circular obstacle.

This hyphae, an example of ‘the snake’, has become trapped in a corner. Image from the authors of the study.

In this example, ‘the zombie’ has brute-forced its way through the obstacle course. Image from the authors of the study.

© Dr Hans Gunter Wagner, Flickr

Medical properties

Initial research shows that Magpie Inkcaps contain potentially beneficial medical compounds.

- Neuroprotectives – protect brain cells and reduce the risk of Dementia, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s.

- Antioxidants – protect against free radicals, reducing the risk of heart disease and cancer.

- Antimicrobials – antibiotics and antifungals.

- Cytotoxins – damage or kill cells, which explains why they are poisonous! They were found to have cytotoxins that were potent against specific cancer cells.

Further research is in progress.

© Robert Stok, Flickr

Spotting them

When to see them: September to December.

Remember to record your sighting if you spot them in Suffolk!

© Lucas Large, Flickr