© Pascal Girard (iNaturalist)

Since the 1970s, the number of eels reaching Europe has declined by around 90% (or more). Their unique life cycle makes them vulnerable to changes in marine and freshwater habitats. They are now a critically endangered species on the global IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.

European eels live long, complex lives, travelling thousands of miles and repeatedly transforming their appearance.

The European Eel Anguilla anguilla is a teleost fish (bony skeleton) and belongs to the superorder Elapomorpha and the family Anguillidae.

Eels have a long lifespan and can live up to 80 years. They are a catadromous species (spending most of their life in freshwater and migrating to sea to spawn).

© Pierre Corbrion (iNaturalist)

They are long and snake-like with tough, slimy skin. Their dorsal and ventral fins run the length of their body and merge at the tail. Eels can be a variety of colours depending on their age and habitat; silver, black, brown or dark olive green in colour above, paler and yellowish on the underside.

© Mattia (iNaturalist)

Adult eels are both predators and scavengers, feeding on dead animals, fish eggs, invertebrates and other fish.

© Dubas (iNaturalist)

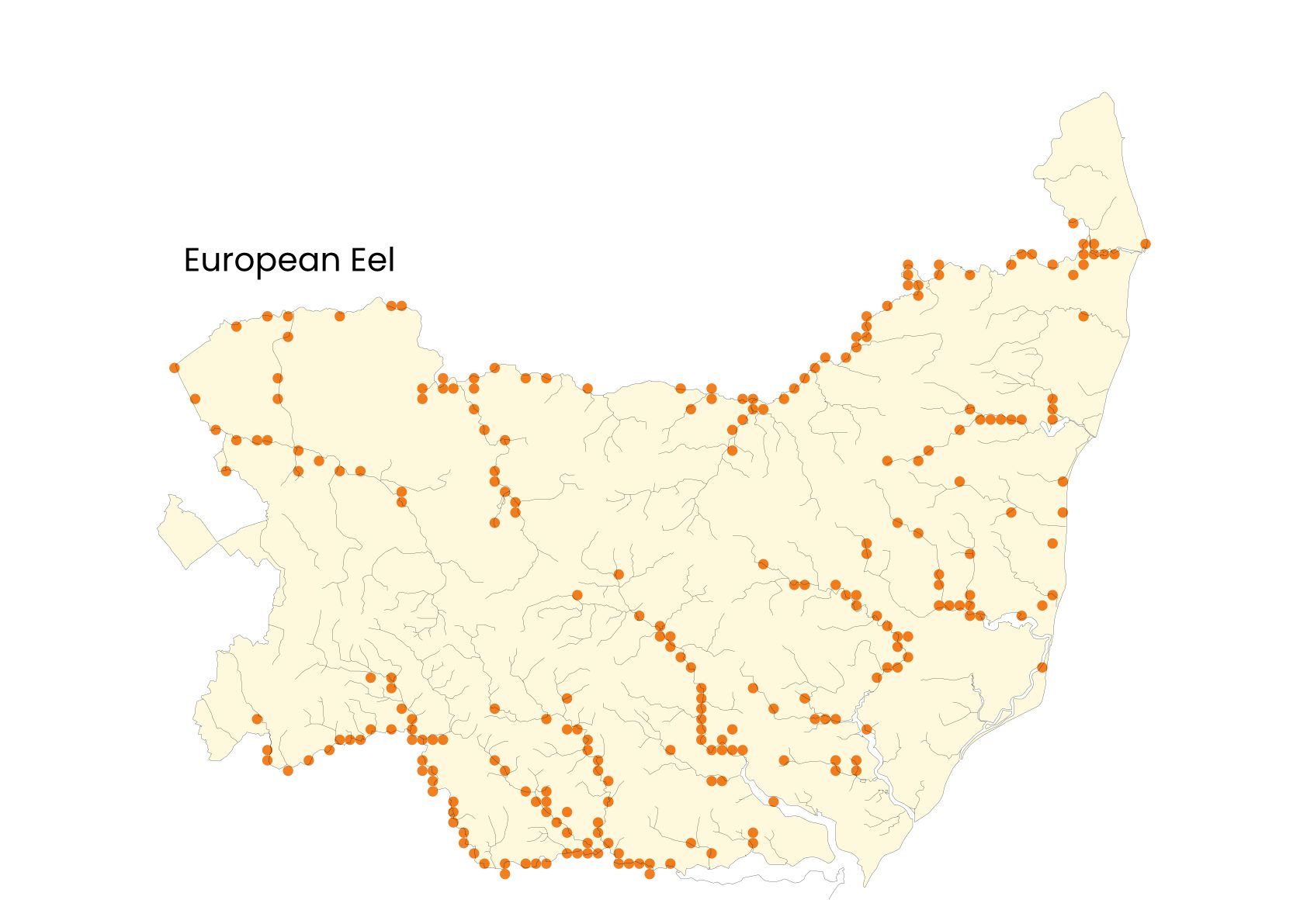

Distribution in Suffolk

Eels can be found on the coast, in low-salinity pools, estuaries, rivers and ditches.

In the Brecks, the Sea to Chalk: Restoring Sea Trout and Eels project is working to remove in-river obstacles and create fish passes on the River Lark to enable the free flow of eels and other fish. Read more here...

Folklore – the origins of eels

Glass eels © Uwe Kils (Wikimedia)

Lifecycle

Spawning

When the eels reach the Sargasso Sea between Bermuda and Cuba, the warmer waters, combined with odour imprinting, signal them to end their migration. Having arrived at their spawning grounds, they rapidly increase gonad development and release pheromones to attract other eels.

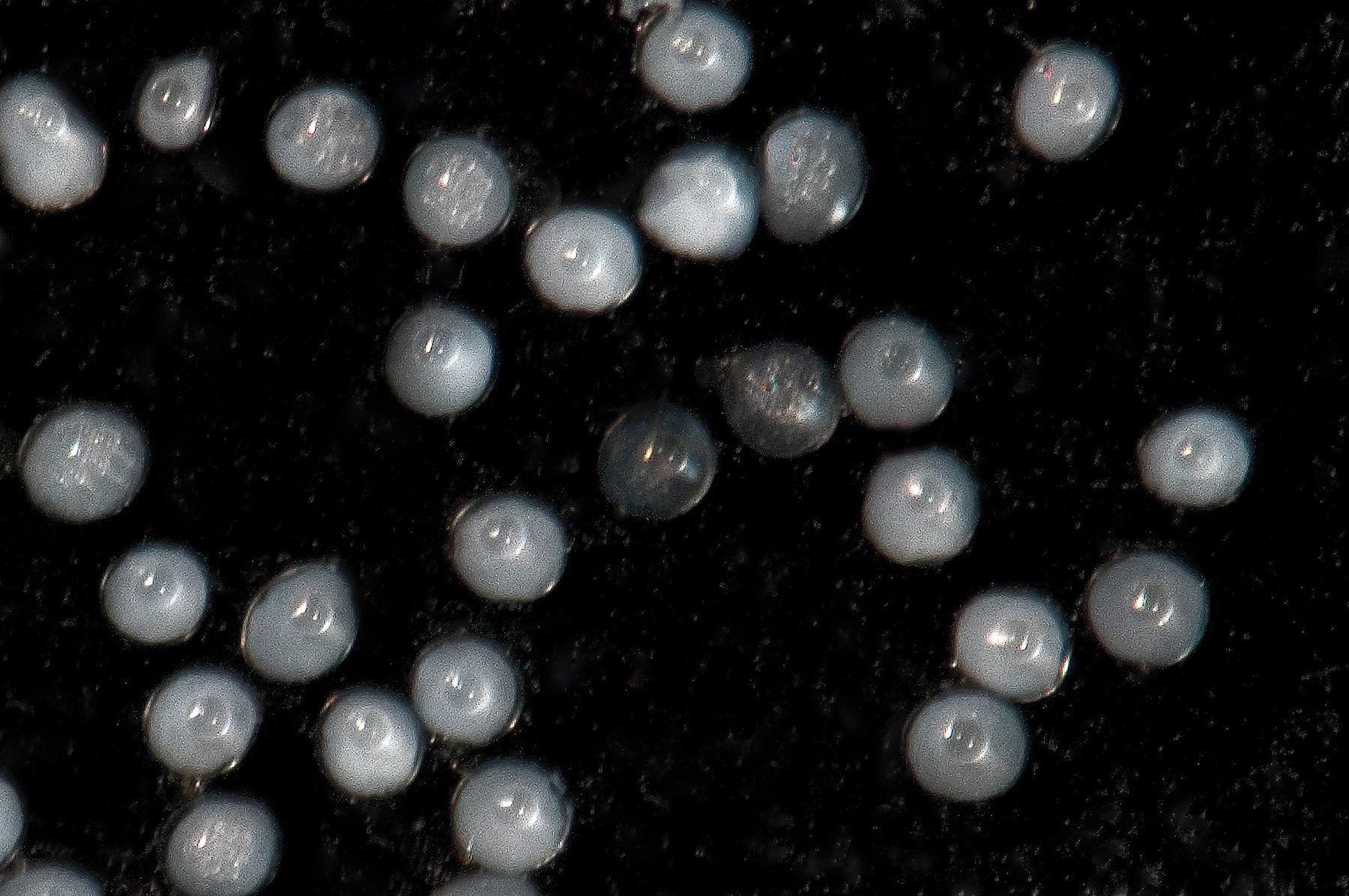

Spawning is thought to occur from March to June and is collective and simultaneous, with each female producing approximately 2-10 million eggs. Afterwards, the mature eels die, and the tiny spherical eggs laid in the Sargassum seaweed hatch into Leptocephalus.

Silver eel

Once they have stored enough body fat (approximately 1/3 of their total body weight), they undergo yet more changes through spring and autumn:

- They become dark grey/green or blue on top, with silver flanks and bellies, creating a countershading pattern that makes them harder to see.

- The eyes become larger and rounder, and the retinal pigments change from green-sensitive to blue-sensitive, presumably to help their deep sea vision.

- The pectoral fins change from a small paddle shape to large, pointed fins.

- Their body chemistry alters to allow them to live in salt water after years of freshwater living.

- Feeding reduces as the gut is absorbed and gonad development begins.

Finally, when the temperature drops in the autumn, they stop feeding and begin their long migration back to their spawning grounds, relying on stored energy alone.

© Fred Fourie (iNaturalist)

Yellow eel

Elvers develop into yellow eels and migrate upstream. Young Yellow eels turn olive/brown on top with a yellow or silver/yellow belly. They become fully adapted to fresh water, produce slime and a toxin in their bloodstream to deter predators and develop the ability to breathe through their skin.

During the day, they spend most of their time lying in holes or flat in the mud with the upper part of their body upright and feeding at night.

Small eels appear to prefer shallow habitats with abundant vegetation, whereas larger eels prefer intermediate to deep water with less vegetation.

© Lindra (iNaturalist)

Elvers

When entering brackish / freshwater, they go into stealth mode, transforming to Elvers and gaining brown pigment for better camouflage in inland rivers and streams. When they reach 8cm, they migrate upstream.

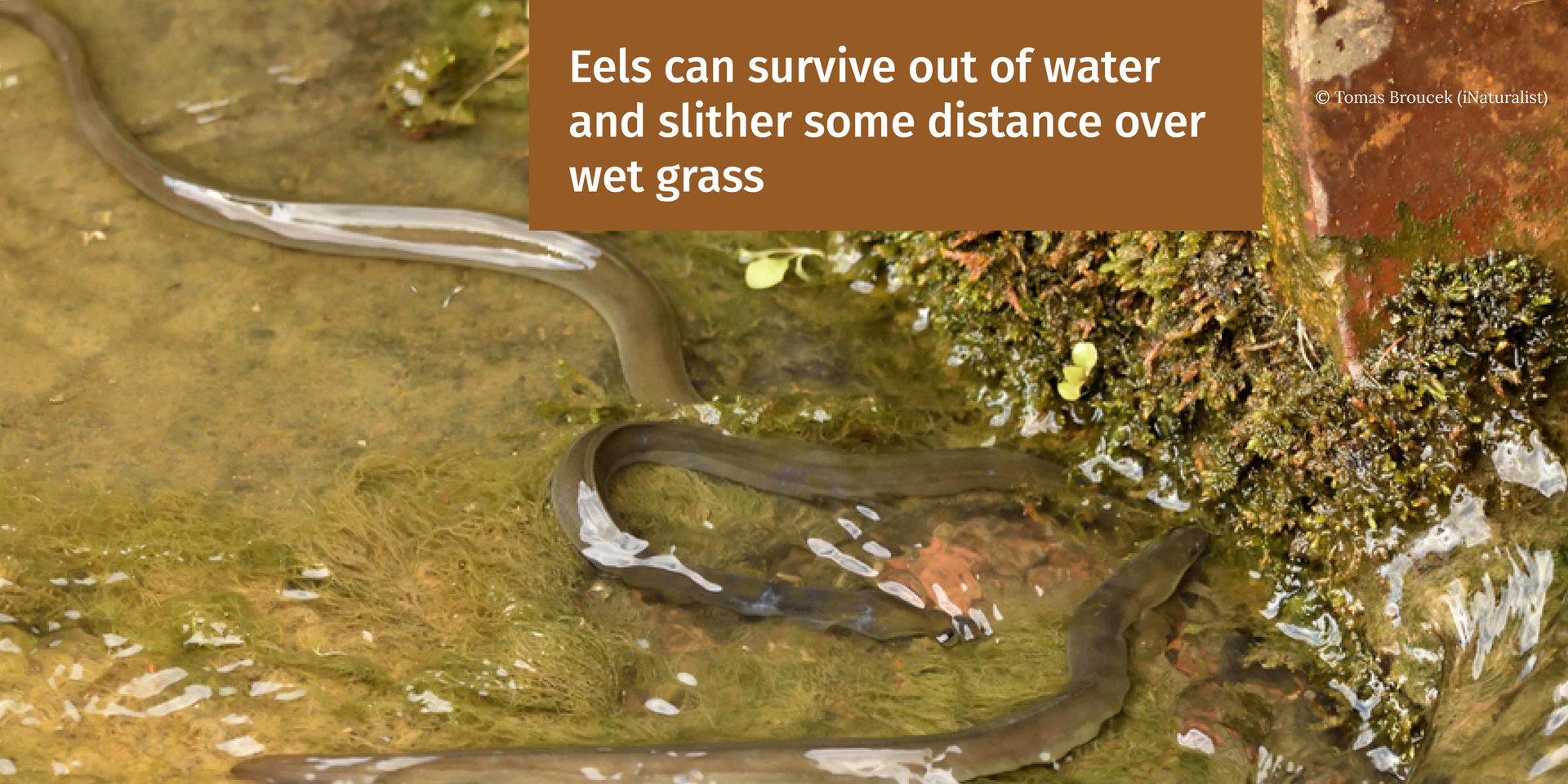

Elvers are relentless in their journey upstream. Leaving the water to traverse fallen branches or rocks that block their path and even cross land.

© Mette Hesselholt Henne Hansen (iNaturalist)

Glass eels

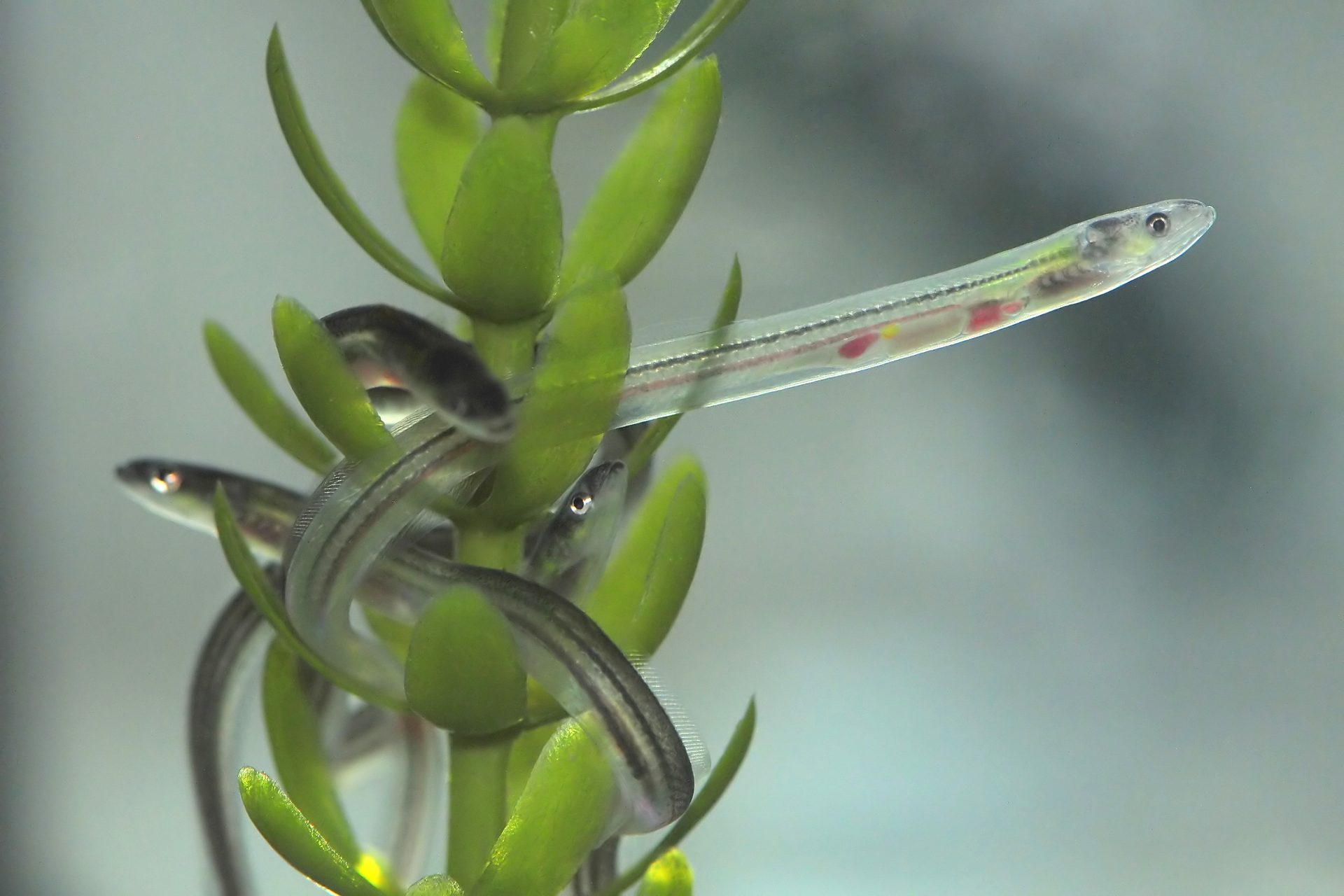

After a year or two of drifting across the ocean, the larvae near the European and North African coastlines. Here, they metamorphose into finger-length, see-through miniature eels – called glass eels – to enter estuaries and make their way inland.

This stage of the eels' lives has caused alarm over the species' risk of extinction, with the number of glass eels arriving in Europe falling by around 95% over the past 40 years.

© Fane Martin (Flickr)

Leptocephlus (larvae)

Until 1893 transparent leaf-shaped larvae were thought to be a separate species, Leptocephalus brevirostris. Although the connection is now well understood, the name leptocephalus is still used.

Their flat bodies are filled with a jelly-like substance, surrounded by a thin muscle layer. Their gut is a simple tube, and, at this stage, they don’t have red blood cells.

They drift passively northeast on the Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Drift Current. However, once they reach 5mm long, they start actively moving between shallow, warmer water at night and deep, colder water during the day. It can take up to two years to complete their journey to UK shores.

© Alexander Semenov (Flickr)

Migration

The European Eel undertakes the longest spawning migration of all anguillid eels, some 5,000–10,000 km across the Atlantic Ocean.

A century ago, Dr Johannes Schmidt proposed that the Sargasso Sea was the Eels’ most likely breeding place.*. Last year, a study of satellite-tagged eels tracked their migration and finally proved his theory.

RSPB Eel tracking study

Very little is known about how adult eels use freshwater habitats. So the RSPB at Slimbridge is working with Bournemouth University to discover more by catching adult eels and implanting them with microchips.

In future, captured eels will be checked for chips to determine if the eels stay in the same ponds for years or if they move around.

It is hoped that the microchips will also shed light on the final stage of the Eels’ lives. In addition, a scanning device has been placed in the ditch that Silver eels use to leave the wetlands and begin their migration, which will scan and record the eels’ details as they wriggle past.

© Sebastien Sant (iNaturalist)

Did you know?

© Vtzanatos (iNaturalist)

Spotting European Eels

They can be hard to spot as they are nocturnal and hide under rocks, weeds, or soft sediments during the day.

When to see: Year-round, however, many eels travel upstream between February and May.

Remember to record your sighting if you are lucky enough to spot European Eels in Suffolk!