Water shrews are the largest species of shrew in the UK, and, like all shrews, they lead a hectic life, constantly searching for food. They are the most adaptable, able to hunt both on land and underwater.

Although they are similar in size to mice and voles, water shrews are more closely related to moles and hedgehogs. They grow up to 10 cm long with a tail length of 8 cm and a weight of 15 – 19 grams.

They have a distinctive two-tone coat, dark above and white underneath, which is exceptionally dense and velvety.

Did you know?

They are the only small mammal likely to be seen swimming underwater in the UK.

They have a white spot just behind their eye and near the small, rounded ear nearly hidden in the fur.

They have a black nose, a long, tapering snout and tiny eyes.

Fringes of stiff hairs on their feet increase their surface area, making it easier to paddle, and they have a keel of long, stiff hairs on the underside of their tails that acts as a rudder.

Top: close up of a shrew's foot

© John Rochester (Flickr)

Bottom: The 'keel' of hair along the tail

© Marina Nikonorova (iNaturalist)

Red tipped teeth

© Vladimir Bryukhov (iNaturalist)

Like other shrew species, their teeth are tipped with red. With their prodigious appetite and near-constant eating, their teeth are subject to a lot of wear and tear.

However, they have adapted to this by depositing iron in their tooth enamel, strengthening it and giving it a red tint.

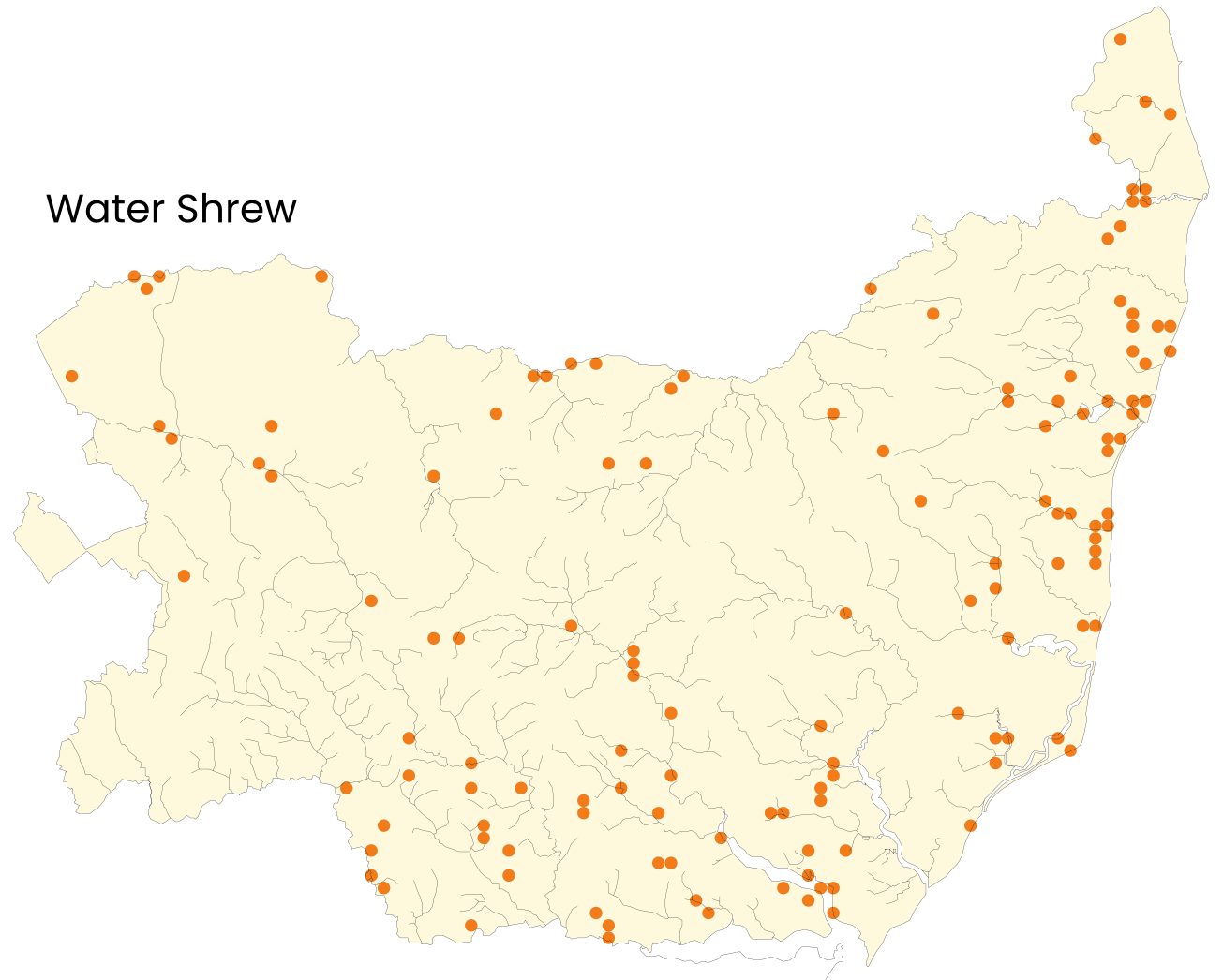

The water shrew is found throughout mainland Britain. However, in some areas, their numbers have declined drastically in recent years, probably due to their habitat's destruction by draining waterways, wetlands, and pollution.

Jowitt, A.J.D. & Perrow, M.R., Suffolk Natural History, Vol. 29 (1993), Desperately seeking ... Water shrew (Neomys fodiens) and Harvest mouse (Micromys minutus) in Broadland.

Distribution in Suffolk

Emerging from a burrow

© Andrew Thompson

(iNaturalist)

Water shrews are often found in clean, freshwater habitats, typically along waterways' banks, including drainage ditches. They also frequent ponds and reed beds. Water-cress beds are particularly favoured for the quality of the water. After the breeding season, they disperse and may turn up far from water, in grassland, scrub, hedgerows and even urban gardens.

Outside the breeding season, population densities are usually low, with around nine per hectare found in good-quality habitats.

Did you happen to know?

That water shrews are very vocal, with squeaks in the ultrasonic range. These high-pitched sounds seem to be used for echolocation in short-range exploration and navigation.

Swimming and diving

Water shrews have a dense coat that traps a layer of air to repel water and insulates them from low water temperatures. However, this results in the shrews being very buoyant, and thus, dives are usually short and frequent as it takes a lot of paddling to remain underwater.

Swimming and diving

© Trevor Goodfellow, Flickr

Diving up to a metre deep to hunt along the bottom of rivers or streams, they turn over stones with their grasping feet, use their touch-sensitive whiskers to detect prey underwater, and then return to the bank to kill and eat them.

Recent research revealed a part of the evolutionary process involved in diving. “We mapped the evolution of a single protein, called myoglobin, that stores oxygen in the muscle,” says Dr Berenbrink. Increasing oxygen storage in the muscles reduces the water shrew’s need to breathe, allowing them to stay underwater longer.

The study provided a fascinating insight into the development of diving behaviour in water shrews, which in theory, are the least equipped mammal for diving.

Walking On Water

© NPS April Henderson, Flickr

Walking on water

Their buoyancy becomes useful when they want to walk on water. The stiff hairs on their feet allow them to use the water’s surface tension to support them.

Did you know?

Water shrews belong to the order Eulipotyphla, which translates to "the truly fat and blind."

Water Shrew on beach in NW Wales feeding on sand hoppers

© Mike Langman (YouTube)

Diet

Water shrews are carnivorous; their primary food source is freshwater shrimps, water skaters and caddis larvae. However, they will also eat frogs, newts, small fish, terrestrial invertebrates – earthworms, snails, beetles – and even small rodents.

© Charlie Marshall (Flickr)

Metabolism

The shrews’ exceptionally high metabolic rate gives them a voracious appetite. As a result, their lives are spent in a constant search for prey, often eating more than their body weight in food each day to satisfy their energy needs.

They will die of starvation if they go without eating for more than three to five hours.

To combat this, water shrews have developed unusual ways to kill larger prey and increase the time they can store food.

© Julian King (Flickr)

Venom

Water shrews are the only European mammal with venomous saliva.

The venom helps them to catch larger prey, up to 60 times heavier than themselves.

It paralyses prey but doesn't kill it, allowing live hoarding.

Research paper

© Iain Dykes (iNaturalist)

Live hoarding

Water shrews move their paralysed prey to a store in their burrow, where it’s kept for eating later. By keeping their victims alive but unconscious, they increase the length of time that they are edible. So, hoarding a food supply can save energy and time spent on prey foraging and catching.

Research papers:

Behavioral Ecology: Prey size, prey nutrition, and food handling by shrews of different body sizes

Left: Water shrew © Braniego Asturcones (iNaturalist) Right: Common shrew © Hanna Knutsson (Flickr) Slide bar to compare

Water shrew or Common shrew?

The Common shrew (Sorex araneus) is smaller and has a shorter tail with a dark brown three-tone coat. If you can get a closer look, you will see that common shrews don’t have the keel of stiff hairs under their tail.

Left: Water shrew © NathDCFC (Flickr) Right: Common shrew (Laurus nobilis) © lizzpostcodegardener (iNaturalist) Slide bar to compare

Water shrew or Pygmy shrew?

The Pygmy shrew (Sorex minutus) is much smaller, has a more domed head and has a reddish-brown coat. If you can get a closer look, you will see that pygmy shrews have a much hairier tail overall but without a keel of silvery hairs on the underside.

Water shrew or Mouse?

Mice are proportionately much bigger, have longer tails, and have more prominent eyes and ears than shrews (shrews have tiny eyes). In addition, mice have a broader and less pointed muzzle.

Water shrew or Vole?

Voles are generally larger, with rounded muzzles and short tails.

© Iain Dykes (iNaturalist)

Spotting Water Shrews

When to see: Year-round.

Signs to look for: Droppings – up to 10 mm long, black when wet, pale grey when dry. Sometimes containing white fragments. Seen on streamside rocks or the entrance to burrows.

Burrows – about 20 mm across, undisturbed vegetation around the entrances.

Remember to record your sighting if you are lucky enough to spot water shrews in Suffolk!