The Hornet Moth (Sesia apiformis) is a large moth native to the UK.

© Ryszard Szczygieł (Flickr)

Their appearance is an excellent example of Batesian mimicry, where a harmless species evolves to look like one that is harmful to avoid predation. Looking like a hornet makes them unappealing to many predators based on a previous unpleasant experience with a hornet or similar species.

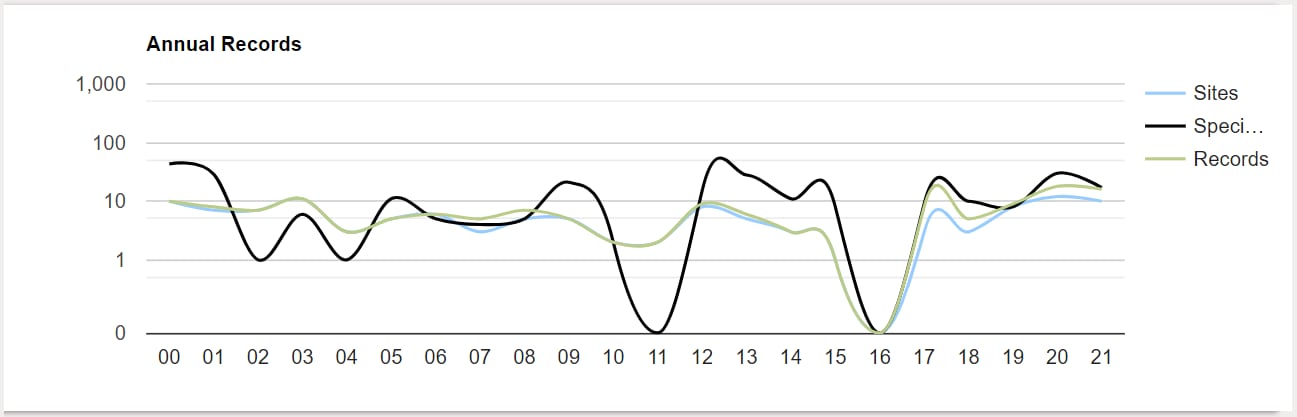

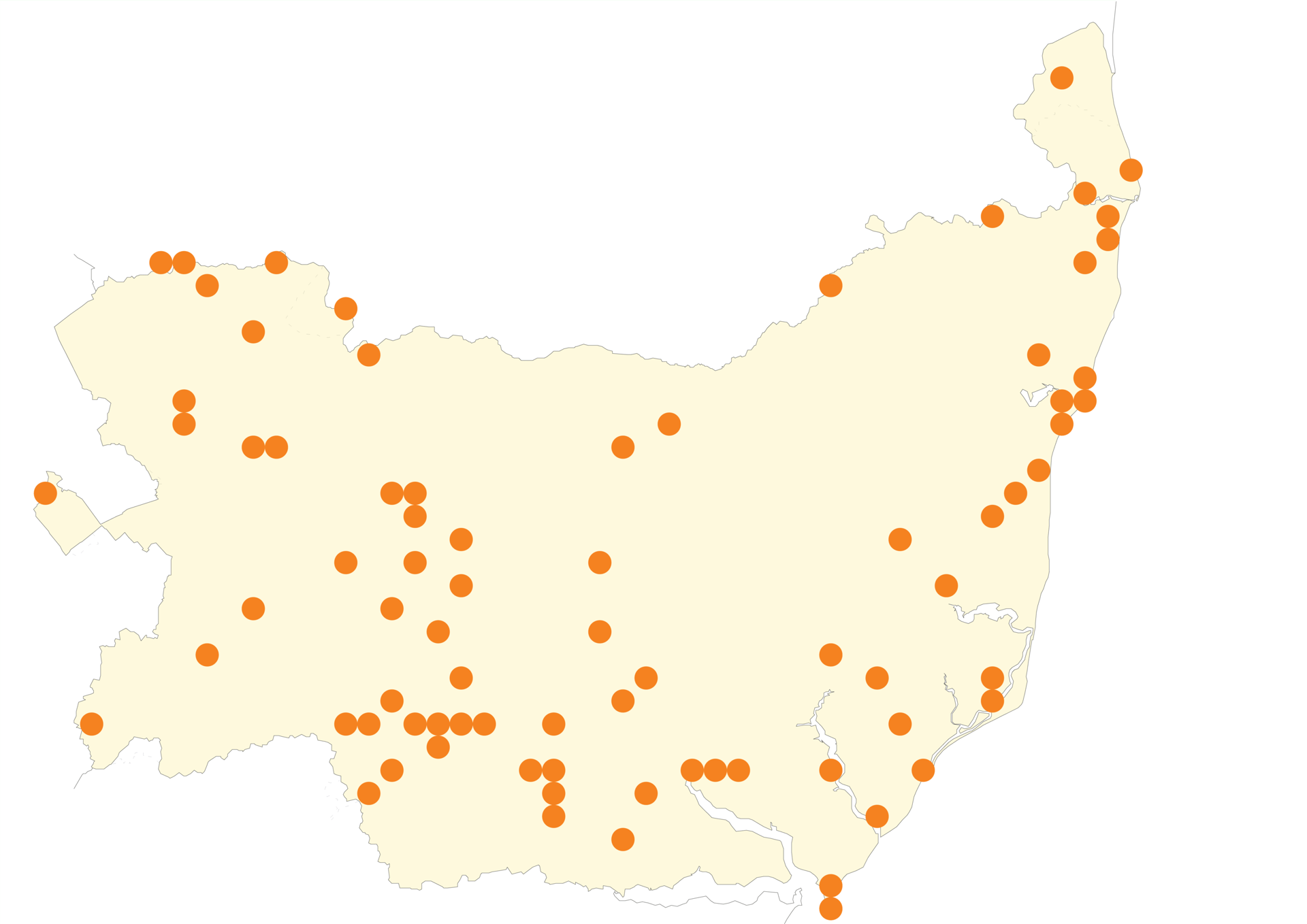

They are not common but can be found across Suffolk, with numbers varying from year to year.

Hornet Moths have clear wings that span 34–50 mm. They have yellow and black striped abdomens, but the number of stripes varies; females have two stripes, whereas males have three. Females are, on average, larger than males. They are the size of a Hornet but can be identified by their feathery antennae, smaller eyes, yellower colouring and chunkier body, lacking a waist between the abdomen and thorax.

© Paul Kitchener (Flickr)

© Paul Kitchener (Flickr)

Hornet

Hornet Moth

Distribution in Suffolk

Habitat

Hornet Moths prefer open habitats such as parks, hedgerows, golf courses, quarries, fens, pond edges and pits, often where trees are in open habitats.

Look for larvae exit holes at the base of trunks

Or empty cocoon casings

© Trevor Goodfellow (Flickr)

Diet

The larvae feed on several species of trees, including Aspen, Black Poplar, Lombardi Poplar and Goat Willow. Adult moths prefer to feed around trees surrounded by heavy vegetation. It was found that trees near heavy vegetation had more significant numbers of larvae than those without vegetation.

© Jose31 (Wikimedia commons)

Conservation

The UK population has been declining over the past couple of decades. While the adults are challenging to observe, the empty cocoons left partially protruding provide a proxy for the number of moths in an ecosystem. For example, in several sites around southern England, no new exit holes were found in trees with existing exit holes, suggesting local population extinction. This, as well as under-reporting, has led it to be classified as nationally scarce in the UK.

A Pest?

Hornet Moths have been considered a primary cause of the dieback of Poplar trees. However, recent evidence suggests that the moth is a secondary threat, with their tunnel-boring larvae magnifying the effects of drought and human influence.

© Paul Kitchener (Flickr)

Spotting Hornet Moths

As Hornet Moths only fly for a few weeks a year they can be hard to spot. Look around the base of Poplar or Goat willow trees to spot their larvae's telltale exit holes and empty cocoons.

If you are lucky enough to spot Hornet Moths don't forget to record your sighting!

© Trevor Goodfellow (Flickr)