Rarely seen during daylight, occasionally spotted silhouetted against the sky at dusk. You are more likely to hear a Nightjar than see one

During the day, they remain motionless on the ground, relying on their cryptic plumage – with feather patterns resembling dead leaves and old tree bark – to protect them from predators.

Nightjars are around 26cm long, with a wingspan of approximately 55cm. Males weigh between 51 and 101g, and females between 67 and 95g.

X

CLOSE

The word cryptic – descended from the Greek kruptikos – means concealed, hidden, secret, or occult. Zoology focuses on the first two definitions and means “serving to conceal or camouflage.” Cryptic plumage, usually subtle patterns of soft browns or greys, is a defensive adaptation; artfully-arranged stripes, spots, or shading breaks up the structural lines of an animal, rendering it visually indistinct.

© Natural England/Allan Drewitt, Flickr

Description

They have greyish-brown upper parts with dark streaking, a pale brown hindneck collar and a white moustachial line. Their closed wing is grey with buff spotting, and their underparts are greyish-brown, with brown barring and buff spots. Their legs and feet are brown.

© Gaetan Mineau, Flickr.

Adults have a flat, broad head, a blackish bill surrounded by long, sensitive bristles, large eyes with a dark brown iris, and excellent night vision.

© Oleg Kosterin, iNaturalist

They have long wings and tails, and, in flight, male nightjars can be distinguished from females as they have a white band on their wings and white tips to the two outer tail feathers. Their soft plumage gives them tremendous buoyancy and allows them to fly silently.

© Óscar Mendez, iNaturalist

© Вячеслав Ложкин, iNaturalist

Did you know?

Nightjars use a unique comb-like structure on their middle claw to preen and perhaps remove parasites.

Song and calls

The male Nightjar’s song is a long churring trill, with 30 to 40 notes per second, lasting up to 10 minutes, with periodic shifts of speed or pitch. It can be heard from 200m away and carries as far as 600m in good conditions. They sing primarily at dusk and dawn and dislike singing in the rain or other poor weather.

They sing from a perch, often moving around their territory to use different song posts. The finale is often a bubbling trill and wing-clapping, perhaps due to a female approaching. However, wing-clapping does not involve contact between the wing tips over the bird’s back. The sound is produced as each wing cracks down in a whiplash-like way.

The female does not sing, but in flight, all nightjars will give a short cuick, cuick call. Other calls include a sharp chuck when alarmed and an assortment of wuk, wuk, wuk, muffled oak, oak and murmurs when on the nest. Adults and larger young birds have a threat display with wide open mouths and loud hissing.

Guy Kirwan, XC657534. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/657534

Graham Clarke, XC657460. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/657460

Huw Lloyd, XC562921. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/562921

Will Scott, XC675386. Accessible at www.xeno-canto.org/675386

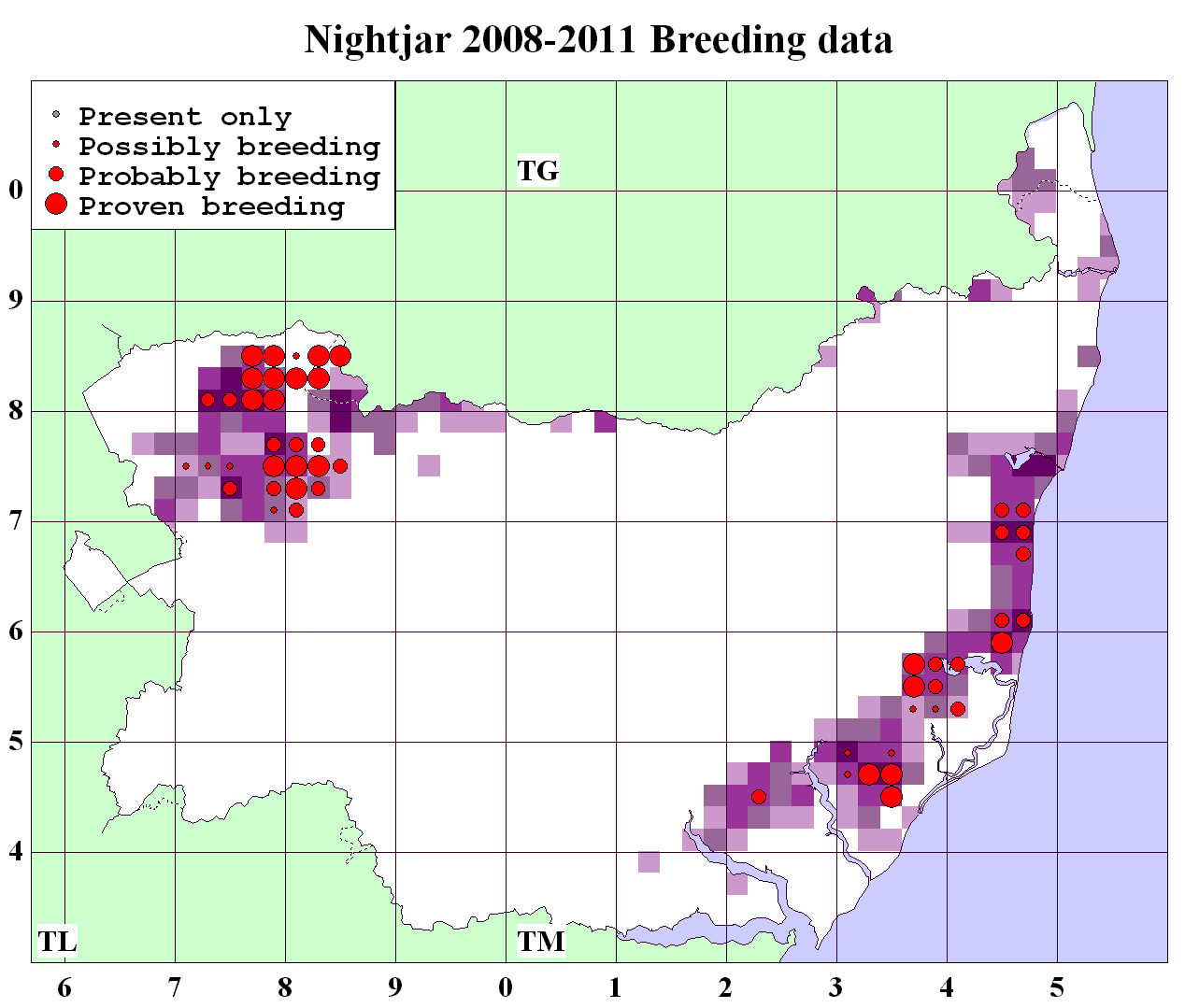

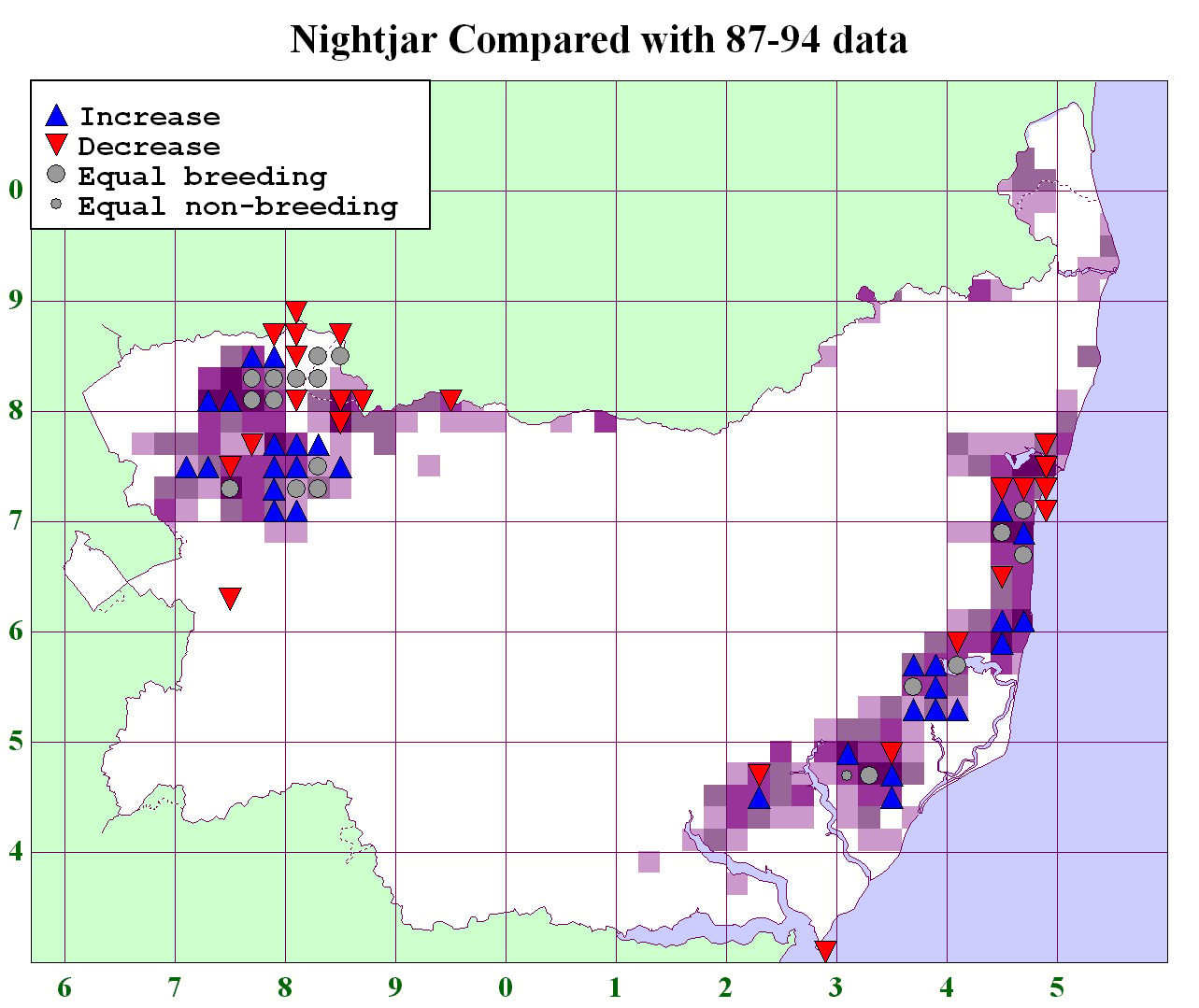

You can find nightjars across much of Britain, wherever there is suitable habitat.

Typically they nest in heathland and young conifer plantations. However, they can also be found in coastal moorland, Sweet Chestnut coppice and sand dunes.

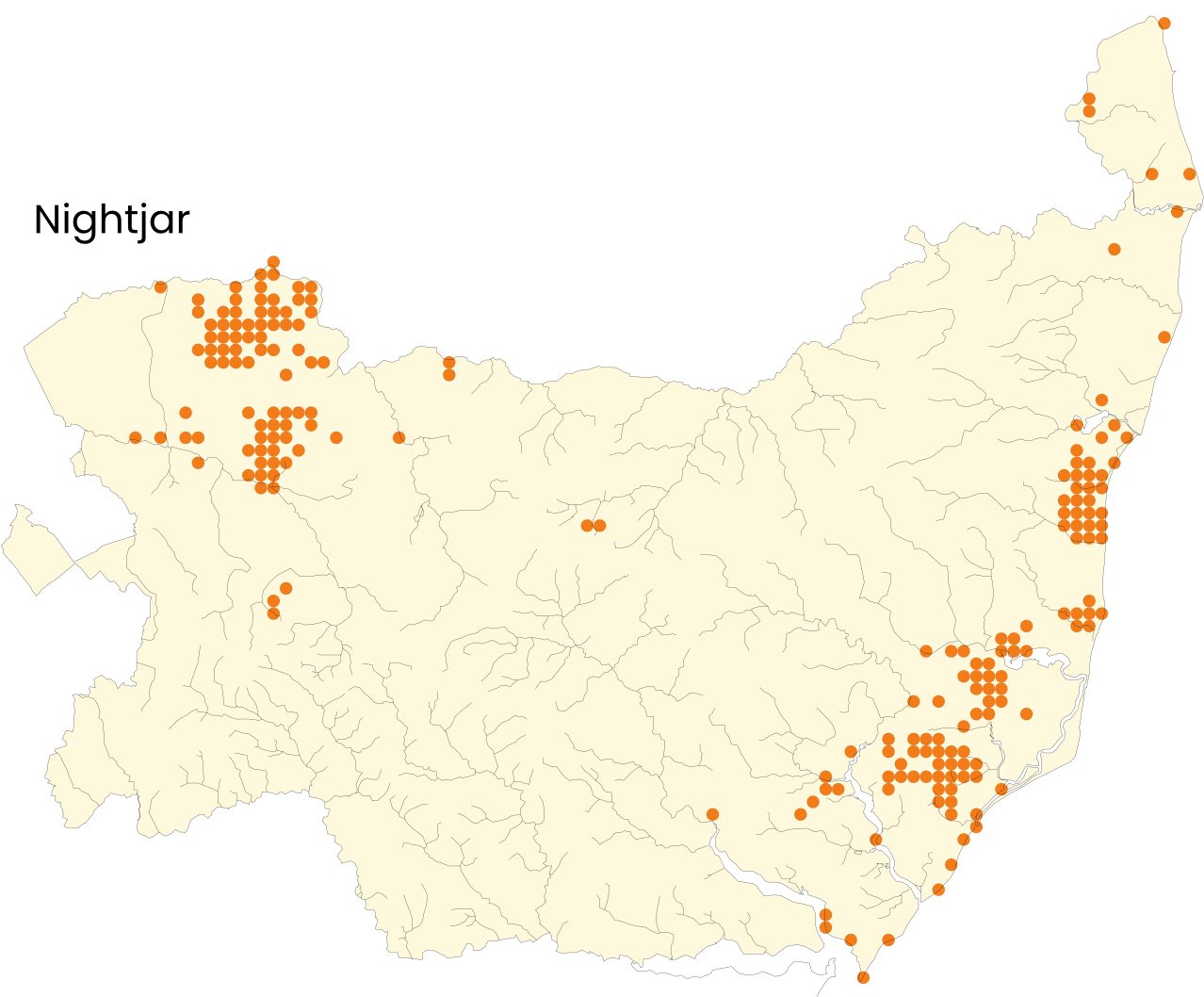

They have been recorded in two distinct areas of Suffolk, along the coast and northwest of the county.

While their population increased by 35 per cent between 1992 and 2004, they are still Amber listed under the Red List for Birds, meaning they are a species of conservation concern. The lack of available breeding habitat is considered a significant issue for them.

- The BTO Trends Explorer shows Nightjar population changes.

- An overview of the year-round movements of Nightjars in Europe can be seen on the EuroBirdPortal viewer.

Distribution in Suffolk

Lifecycle

© Chris Moody, Flickr

Nightjars arrive in the UK from southern Africa during the spring, usually around April-May and spend the summer months here before migrating back during September.

They usually breed from late May to August. They do not build a nest but instead lay eggs directly on the ground among plants, tree roots, or beneath a bush or tree. The nest site may be bare ground, leaf litter or pine needles. It is often reused for several years. They lay one or two eggs, usually speckled with browns and grey, and will have one or two broods.

Their cryptic plumage is invaluable in disguising them from predators during their 18-day incubation period. The female does most of the work, but the male stays nearby and will sit on the eggs for short periods around dusk and dawn. The chicks fledge around 17 days after hatching, have downy brown and buff plumage, and, once fledged, look similar to adult females.

Ira Han, iNaturalist

In 2018 Ben Locke was lucky enough to observe a nightjar nest in the Forest of Dean and documented these highlights of chick rearing.

Adults moult their body feathers after breeding, pause the process while migrating, and replace their tail and flight feathers once they reach their wintering grounds, where their moult is completed between January and March. Immature birds follow a similar moulting pattern to the adults unless they are from a late brood, when the entire moult may happen after migration.

The typical lifespan for a Nightjar is four years. However, the BTO’s oldest recorded Nightjar from ringing records was 12 years old.

The Nightjar’s diet comprises invertebrates, including moths, flies and beetles. Like other birds, they will also eat grit to help their digestion.

They spend nights hunting by sight, silhouetting their prey against the night sky and catching it on the wing. Made easier by its wide mouth and silent flight. Tracking experiments have shown that feeding activity more than doubles on moonlit nights.

Male Nightjar showing his massive mouth.

© Valia Pavlou, iNaturalist

Diet

© Alan Shearman, Flickr

Did you know?

The Latin name for the Nightjar means ‘goatsucker’. They were believed to feed on goat’s milk as they were often found close to them. We now know that they feed on the invertebrates associated with livestock.

Nightjars are crepuscular (active at dusk and dawn) and nocturnal (active at night). During the day, they rest on the ground, often in a partly shaded location, or perch motionless lengthwise on a branch or a similar low perch. If they are not already in the shade, birds on the ground occasionally turn to face the sun to minimise their shadow. If they feel threatened, they flatten themselves to the ground with their eyes almost closed and don’t move until the threat comes to within 2–5m.

Nightjars can slow their metabolism and enter a state of torpor in cold weather. Captive Nightjars have been observed to maintain a state of torpor for up to eight days without harm, but it is unknown if birds in the wild can do the same.

Behaviour

© _paVan_, Flickr

How the moon influences Nightjars...

Strolicfurlan, Flickr

Egg Laying

A 1996 study revealed that the phase of the moon influences the timing of egg laying.

“European Nightjars laying in June will be feeding young in July and also may initiate a second clutch in July. For these birds, which form a substantial proportion (ca. 50% from Nest Record Card Data) of those laying their first clutch in a season, the energetic advantage of laying during a waxing moon could facilitate the production of a second clutch under similar lunar conditions.”

“Typically, they seem to lay their second clutch when the first brood is two weeks old (chicks do not fledge until they are 16-17 days old and are dependent on their parents for a further 16 days or so ... [it has been] shown that a female may switch between mates, leaving her first male with the first brood while taking a second male to assist with the second attempt. Laying at that stage in the previous nesting cycle results in consecutive clutches being laid some 30 days apart, very close to the lunar cycle of 29.5 days.”

The authors concluded that the nightjar’s nesting cycle may have evolved to benefit from full moons at three critical points:

- At laying;

- When the young are one to two weeks old;

- When the young are newly independent at six weeks old.

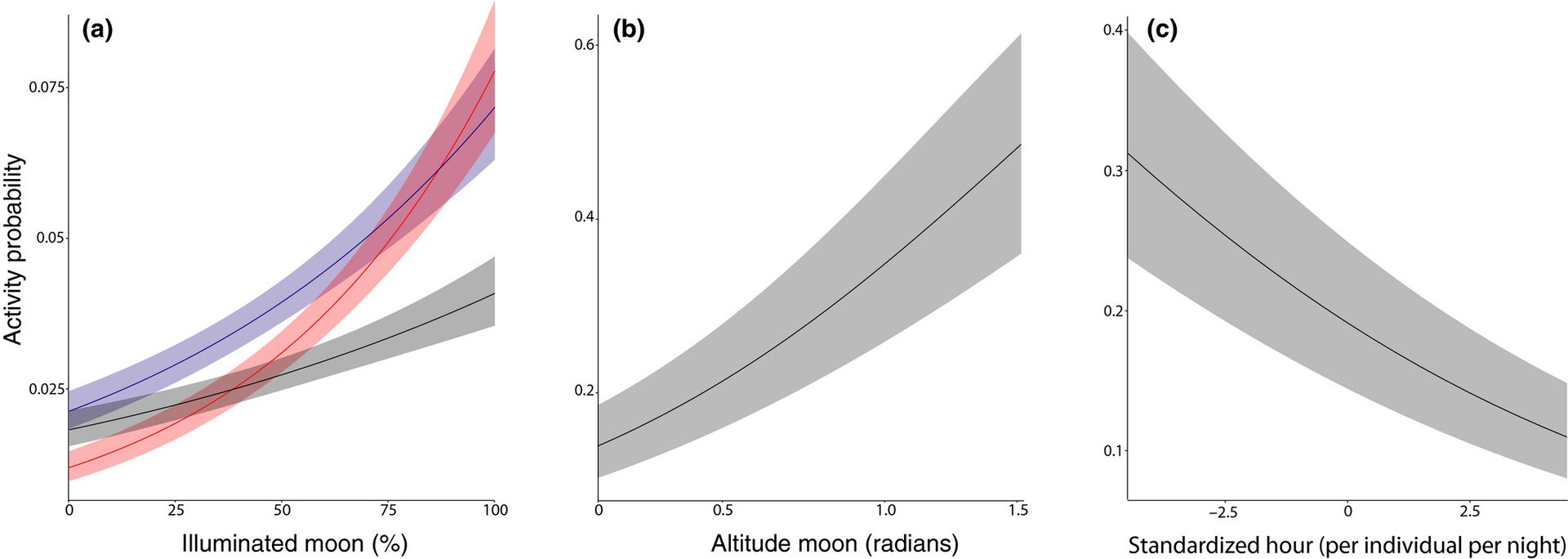

Activity Patterns

This study explored the lunar cycle’s effect on Nightjars’ nocturnal flight activity. They found that average individual flight activity clearly correlated with variation in day length and the lunar cycle.

- All individuals showed clear activity peaks around dusk and dawn, confirming the crepuscular behaviour of the species.

- They showed an evident change in nocturnal activity during each lunar cycle, with the peak around the full moon, and they were most active from the lunar cycle’s first to last quarter.

- Their nocturnal activity strongly depended on the fraction of the illuminated, visible moon and its altitude above the horizon, both in the breeding and non-breeding season.

- Activity grew with increased moonlight, the exact amount differing between individuals. Activity levels were also linked to the moon’s altitude above the horizon. Furthermore, their nocturnal activity was significantly higher during the breeding season.

- During twilight, activity was higher at dusk than at dawn and higher during the breeding season than during the non-breeding season. This twilight activity was independent of the moon phase.

The study indicates that nightjars are sensitive to relatively subtle changes in ambient light conditions and predicts that artificial night lighting, especially skyglow during overcast nights, will influence nightjar behaviour. With artificial lighting mimicking a moonlit night, it could potentially improve foraging conditions.

Migration

The New Scientist reported on this study, which explored the moon’s role in Nightjar migration.

“Gabriel Norevik at Lund University in Sweden attached tracking devices to 39 European nightjars. Some of these devices measured the birds’ position using GPS, while others tracked their acceleration. This allowed Norevik and his team to record location over the year and flight activity levels night after night.”

“Their results reveal a key role of the full moon in the nightjar’s itinerary, which consists of long night-time flights with daytime resting punctuated by much longer rests at stopover sites. On moonlit nights, the birds’ foraging during migration stopovers more than doubled.”

“Then, as the moon wanes, increasing numbers of nightjars embark on flights along their migration route, peaking at around 11 days after a full moon. Sometimes, all of the tracked birds would migrate simultaneously at this time in a great pulse.”

“The team also found that the birds concentrate their feeding activity at dawn and dusk on most nights, only foraging through the night when there is plenty of moonlight.”

Norevik says he and his team were astounded by how well the activity pattern of the birds followed the cycles of the moon. This is the first time moon phase has been identified as a regulator of migration schedule.”

Spotting them

When to see them:

late May to mid-August

Remember to record your sighting if you hear or spot them in Suffolk!

© Justina Baigyte, Flickr